It’s time I let you in on a secret. I fantasize all the time. I have wild, indulgent fantasies that sometimes go on for days and would make a hedonist blush. They’re detailed, vivid thoughts of sometimes sordid, occasionally illegal, always climactic experiences. I have these fantasies when I’m falling asleep at night, when I’m taking a shower, and especially when I’m cooking dinner. You see, these fantasies, believe it or not, are about food.

We’ve all had the occasional Iron Chef narrative run through our head as we toil away in the kitchen–the disembodied voice of Alton Brown commenting on the deftness of our knife strokes and pungent smell of our chiffonaded herbs, occasionally tossing in his prediction of our intent: "I believe the challenger is making . . . yes, that looks like a blanquette de veau." However, my fantasies are usually about a meal, the meal, in which all of my wildest wet food dreams materialize, if only for one supper. The strange part is that the fantasy comes in two flavors.

Fantasy #1 is what you might expect from me if you’re a regular reader: Ferran Adrià and a cadre of other chefs put on a modernist feast that lasts for hours and requires a team of 50 to prepare. The "kitchen" is stocked with colloid mills, spray freezers, centrifuges, particle accelerators, and at least one flux capacitor, which is critical to correctly execute the palate-cleanser between the 16th and 17th course. The dishes that emerge are full of surprises and textural transformations. There’s a non-Newtonian truffle foam that coyly evades my fork’s stabbing advances. Hand-sculpted lickable crystals, arranged in homage to Superman’s fortress of solitude, are shattered tableside to reveal a lilac fog that rolls over a champagne-fed morel-mushroom edible landscape. The spherified tears of a Siberian white tiger are served in orchid cups, topped with a magnetically insulated coconut plasma. The foods seem to defy the laws of physics, and flavors are so bold, vivid, and unexpected that I do a double-take with each bite. As I’m eating, I cleverly reverse-engineer the complicated processes that transformed the rare and exotic ingredients into the high-concept, impressionist dishes that emerge in a never-ending sequence from a buzzing stark-white kitchen.

Fantasy #2 is different . . . in fact, quite the opposite. I’m in a country house, sitting at a large wood table resawn from the heart of a felled tree. Just outside, embedded in the acres of manicured landscape, are rows of vegetable beds growing the most beautiful and succulent herbs, lettuces, red beets, potatoes, cauliflower, legumes, and carrots I’ve ever seen. On a shady patch of land dominated by a century-old evergreen, 10,000 wild mushrooms poke up from the soil, already washed clean by a passing morning storm. Near the house, a brown hog is slurping peacefully from his trough of maple syrup, 30 year-old brandy, and charred applewood. Later, when I visit him with my knife, he turns gleefully onto his back to offer me a slab of bacon from his ever-healing belly. On the rolling hills in the distance, a flock of argyle sheep have been standing guard outside the naturally dehumidified cave in which they age the wheels of cheese they lay each spring. In the kitchen, a silent chef wielding no more than a blade and an iron skillet prepares a feast over a wood fire. The dishes are simple and pure, requiring no seasoning except a generous lump of golden raw butter, churned à la minute.

First, a scramble of eggs, already fluffy and lightened by the hens’ daily intake of fresh Jersey cream. Next, a steaming plate of roasted root vegetables–carrots, beets, turnips, radishes–with colors so vibrant and pigmented that they stain the white platters. Then a soup of green peas, roasted porcinis, and cured ham. Loaves of crusty bread emerge from the crackling wood oven, glistening with flaky salt mined from a Himalayan boulder deposited by a passing glacier two million years ago.

Reaching for his ingredients, the chef opens the refrigerator door, which is actually a pass-through into the farm where a quartet of sage-coated border collies have been laying out the mise en place for the meal. The chef picks up a decadently marbled tenderloin which has been dry-aged by the wing flapping of swans and tenderized by the gentle, rhythmic humping of a dozen field mice. He sears the steak perfectly, releasing tears of demi-glace which I spoon atop a snowy-white mash of russet potatoes, already flavored by the Provençal herbs with which the land is fertilized monthly. Every dish is unadulterated, every ingredient is clearly identifiable. The flavors define purity, and the terroir is a tangibly connective thread throughout the meal and its backdrop.

I’m not the only one who has fantasies like this. At last night’s release party for the book "Growing a Farmer: How I Learned to Live Off the Land" by Kurt Timmermeister, 200 people showed up to thank Kurt for making their fantasy #2 come true. For the past five and a half years, Kurt has served a Sunday dinner at his farm house on Vashon Island. And although he may have different methods for aging his beef than those I picture in my fantasy, his dinners have evoked the same emotion. All the ingredients (with very few exceptions) come from his 13 acres, and the food is transformed as minimally as possible on their short journey from his farm to his table. I wrote about my dinner experience there some time ago, but listening him speak last night, I couldn’t help but wonder if there is some amount of tension between my two fantasies.

Lots of folks have raised concerns that modernist cooking (or "molecular gastronomy," as it is often called) is an aberration or a perversion of cuisine, and that the chemicals used in the process are inherently unworthy of ingestion. After all, it takes a fair amount of manipulation to turn an olive into a powder, a gel, a sphere, a foam, or a flash-frozen tuille. Standing among a roomful of Kurt’s fans, I imagined how they would respond if I gathered up bushels of farm-fresh produce and proceeded to cryo-fry it in a vat of liquid nitrogen. My guess? They’d find other uses for the pitchforks besides shoveling hay.

Then, I imagined what it would be like at a release party for a modernist chef’s memoir. I’ve recently been reading the latest biography of Ferran Adrià, and I know his followers would attend in droves, bringing equally strong sense memories of their Fantasy #1-like experiences at el Bulli. Ferran is credited for contributions to cooking in the way Einstein is recognized for contributions to physics, and without his genius, the cutting edge of cuisine today may not have evolved past the iceberg wedge salad. Outside a small set of emerging modernist techniques, Western civilization has been cooking the same way for several hundred years. Yes, it is novel in 2011 to eat an entire meal gathered from a few acres of land, but for most of human history, you had no other choice.

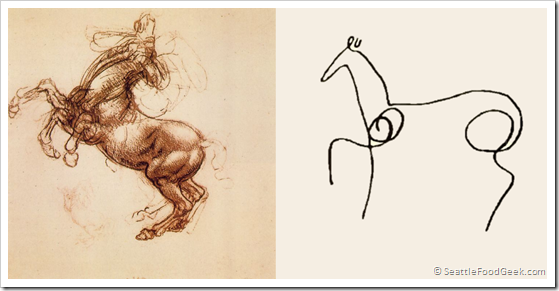

Is there a tension between my two fantasies? No, not at all. If done with integrity, there’s plenty of room for both approaches. For example, I admire the anatomical realism of da Vinci’s drawings, or the way in which Vermeer accurately depicted natural light. But I also appreciate the emotive reinterpretation of the subjects in Picasso’s paintings or the stylized exaggeration in Modigliani’s portraits. In the same way, I love raw butter churned from the fresh cream of a happy cow, and the powdered bone marrow you might choose to sprinkle on top. Modernist cooking is not opposed to farm-to-table; in fact, I would bet Ferran’s groupies would love a dinner at Kurt’s. However, modernist cooking is new and new things scare a lot of people–especially people with limited information. Try this experiment: Tell your friends you’re getting into modernist cooking and so seasoned their food with sodium chloride, which you ordered off the Internet. Count the number of friends who freak out (they weren’t paying attention in 8th grade chemistry, or they’d know sodium chloride is table salt).

I’m glad that these two movements are happening simultaneously. It indicates that we as a society are starting to care more about what we eat and how. In a nation that has become monopolized by industrial food production, our own apathy is our biggest weakness against better eating. Although Kurt’s dinner series has ended, we’re lucky to live a short drive from some of the best small farms in the country . . . and they serve dinner too. Go eat something that was just picked from the ground, or just slaughtered for your dinner. Then go eat something modern and unexpected, designed to challenge your preconceptions. When dinner is over, you’ll have all-new fodder for your food fantasies.

![Growing a [Modernist] Farmer](https://seattlefoodgeek.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/electric-bacon-1.jpg)

New post: Growing a [Modernist] Farmer discusses modernist cooking versus the farm-to-table movement https://seattlefoodgeek.com/2011/01/growi…

RT @seattlefoodgeek: New post: Growing a [Modernist] Farmer discusses modernist cooking versus the farm-to-table movement http://bit.ly/ …

RT @seattlefoodgeek: New post: Growing a [Modernist] Farmer discusses modernist cooking versus the farm-to-table movement http://bit.ly/ …

You transported me, Scott. Great writing.

I have just discovered your blog and this post speaks to me, it actually speaks for me.

Thank you for that.