Update: Thanks to keen reader Edsel for pointing out that ModernistPantry.com is now selling WRISE. This recipe was written for the standard version of WRISE, but they’ve recently introduced an aluminum-free version as well.

I promised myself that, before the summer is over, I would learn to make fabulous pizza at home. It turns out, making pizza at home is a fascinating problem. Almost everyone I know eats pizza at home, but hardly anyone makes it… unless you count baking a frozen DiGiorno or putting toppings on a pre-baked crust. My self-challenge encompasses aspects of both innovation and practice, and with a food as technique-centric as pizza, there’s no getting around the need to practice. I’ve made about 30 pizzas so far this summer, and my technique and confidence increases with each one. However, I’ve recently made a breakthrough in recipe development that shows serious promise: no-yeast, no-rise, Champagne-flavored pizza dough that you can make from start to finish in under 40 minutes. [pictured above]

Seriously. 40 minutes, from scratch. Minute 1: turning on the oven, taking out the stand mixer and grabbing a bag of flour. Minute 40: eating a goddamn delightful pizza.

The secret to this recipe is microencapsulated leavener – a fine powder made of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and sodium aluminum phosphate that have been microscopically sheathed with non-trans palm lipid to prevent them from reacting with surrounding any acid until they are heated to the point at which the lipid coating melts away. This means that the leavening action of the baking soda doesn’t kick in until the pizza is heated, and unlike yeast-based doughs, there’s no need for the dough to rise ahead of time.

The secret to this recipe is microencapsulated leavener – a fine powder made of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and sodium aluminum phosphate that have been microscopically sheathed with non-trans palm lipid to prevent them from reacting with surrounding any acid until they are heated to the point at which the lipid coating melts away. This means that the leavening action of the baking soda doesn’t kick in until the pizza is heated, and unlike yeast-based doughs, there’s no need for the dough to rise ahead of time.

I first read about encapsulated leaveners in Cesar Vega’s fantastic book, The Kitchen as Laboratory. Tom Tongue, the R&D Director at Innovative Food Processors contributed a chapter that discusses the use of these products in commercial, take-and-bake pizzas. I was immediately fascinated by the concept and tracked down a sample package of WRISE from The Wright Group.

In my first tests, I simply added a bit of WRISE to a traditional pizza dough recipe (actually, the Neapolitan pizza dough recipe from the upcoming Modernist Cuisine at Home, to which I have access, neener neener). Although you’ll need to buy the book to read the full recipe, it relies on yeast and a rise time of at least one hour before baking.

A few weeks ago, Cesar Vega and Alex Talbot (IdeasInFood.com) happened to be passing through Seattle and joined Jethro and me for dinner at my place. Among other things, we made pizza using the yeast + WRISE method, and I let the dough proof at 55°F for 6 hours before rolling out the crusts. The pizzas were great, but Alex was quick to plant a nagging question in the back of my mind: why do we need yeast in the dough if we have another source of leavening already? It was a great question, and one I couldn’t shake. The yeast and leavener combined to create an extraordinarily light and puffy pizza crust, which I loved, but presumably one could generate enough lift from the leavener alone. Of course, yeast adds flavor to the dough, but flavor can come from lots of sources other than yeast. Buttermilk, whey, blue cheese, soy, miso, beer, and a dozen other foods could stand in for yeast to produce an interesting dough. Then, Alex threw down another challenge: make a new batch of dough, and bake it without letting it rise to see just how much lift the encapsulated leavened provided.

So I did. The dough recipe takes 20 minutes to make, which includes 10 minutes of rest time in between 5-minute kneading cycles in the stand mixer. As soon as the second knead was done, I portioned the dough, stretched it into a 12-inch crust, and threw it in my 850°F grill-turned-pizza-oven (more on that later – it’s badass). The dough rose, but not nearly as much as the yeast dough that had been left to rise for several hours. A few bites into this “test” pizza, I realized that there was very little acid in the dough with which the sodium bicarbonate could react, which would explain the measly rise. The only acid, in fact, came from a small amount of honey. The liquid content of the dough was all water. The next logical step was to replace the water with a flavorful, acidic liquid and see what happened.

Over the next few weeks, I went to work testing yeastless, WRISE-only dough variations. Now, this is probably a good time to explain that I’m a shitty baker, and my scientific knowledge of the processes that take place inside wheat doughs is limited to some light reading on Wikipedia. However, there’s nothing like empirical experimentation to help me learn my way around a concept, so I have no problem conducting experiments to which a wiser man may already know the outcome.

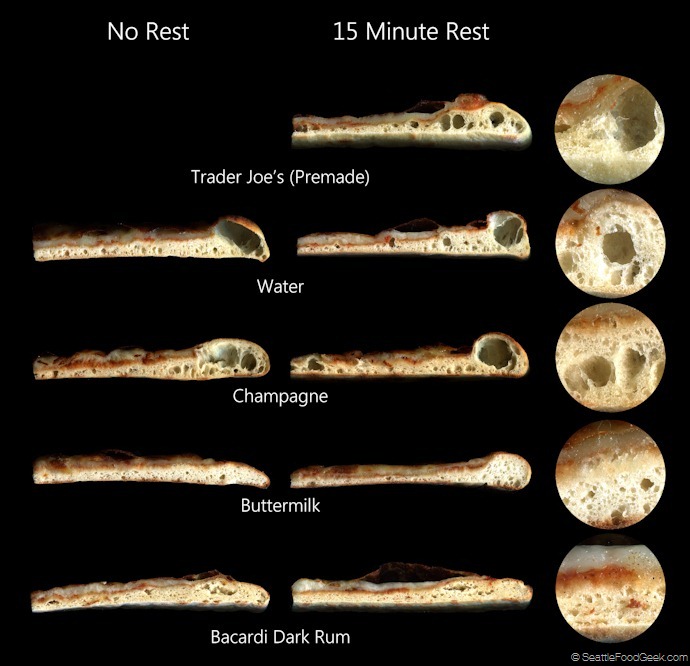

My experimental setup is as follows. I preheated my oven to it’s highest setting (around 550°F, according to infrared thermometer readings) for one hour, with a 25-lb, 1/4” thick stainless steel plate set on the top rack. As described in Modernist Cuisine and Modernist Cuisine at Home, a steel plate makes a fantastic pizza stone. It has a greater thermal capacity than ceramic stones due to it’s higher density, and the higher coefficient of thermal conductivity means that heat can move out of the steel and into the crust faster than it can from a ceramic stone. I divided each dough recipe into two 200-gram portions, and stretched them as thinly as I could while still maintaining their integrity (no holes). I rolled, stretched, topped and baked one portion of the dough as soon as it came out of the mixer (left column in the image below). I let the second portion rest for 15 minutes at room temperature to allow the gluten to relax (right column in the image below). I topped each pizza with 15g of store-bough pizza sauce and 100g of shredded mozzarella cheese. Nothin’ fancy here, just aiming for controlled conditions across my tests. As a control for yeast-based dough, I used a bag of Trader Joe’s premade pizza dough, which calls for a 15-minute rest before using, as it comes refrigerated from the store.

My goal was to achieve a flavorful, well-risen dough by varying the liquid content across trials. Besides the liquid, the recipe for each of the doughs was exactly the same. I specifically chose acidic liquids so that the encapsulated baking soda would have something with which to react to produce the CO2 gas that fills good pizza dough with lovely pockets of emptiness. Each of the pizzas took between 3 and 4 minutes to bake in my oven. I ascribe the time differences to cycle timing of the broiler element in my oven – when the broiler is on, the pizza bakes much faster than when the broiler is clicked off. Here are the results from my trials:

Trader Joe’s Premade Pizza Dough [Control]

[Pictured top-right] This made a totally decent pizza crust. It rose well, it was easy to stretch out into 12-inch rounds, and if you live less than 12.5 minutes from a Trader Joe’s, you can theoretically make pizza faster than with the from-scratch method below. [12.5 minutes x 2 (round-trip) + 0 minute theoretical parking, shopping and checkout time, + 15 minute rest period = 40 minutes.] Observe the relatively large number of big air pockets and the even rise around the crust.Water

This trial, which you could also consider a control, I suppose, used 100% filtered water as the liquid content of the dough. Much to my surprise, it rose pretty well! As you can see in the recipe below, the only acid content is 4% honey, but the dough still lifted itself into a respectable pizza with a spongy texture and decent, though unremarkable, flavor. I’m still a little shocked that the dough had this much lift from the acid in honey alone.

Champagne (er, Sparkling White…) – Winner!

In this trial I used a $5.99 sparkling white wine from Trader Joe’s as the liquid content of the dough. I was counting on the acidity of the wine to react with the sodium bicarbonate, but naively hoping, as well, that the carbonation of the wine would add lift to the baked pizza. It’s unclear that the carbonation did anything useful (all of the gas was likely released during the mixing process), but the “champagne dough” performed like a champ. The flavors of the wine were easy to identify in the finished pizza, and the yeastiness you expect in dough was replaced by the similar yeastiness from the wine’s own fermentation. I could detect apricot and cherry flavors in the pizza, even with the cheese and sauce present. If topped with muscat grapes, and a wine-friendlier cheese than mozzarella, this could be a smashing success. I’m excited by the variations that I can achieve using different sparkling (or non-sparkling) wines and more interesting topping combinations.

Buttermilk

I had high hopes for buttermilk. Buttermilk is mildly acidic (pH around 4.5), but acidic enough that the encapsulated leavened readily foams if heated to 60C in the stuff. Buttermilk is also delicious, with a wonderful sourness that I admire in pancakes and biscuits. Unfortunately, [in this recipe, at least] it made very pathetic pizza dough. Buttermilk must somehow interfere with the formation of the gluten network in the dough, preventing it from holding on to much of the expanding CO2 gas released by the leavener as the pizza bakes. The dough was still quite tasty, but unfortunately didn’t meet the criteria I was looking for in terms of rise. Bummer.

Bacardi Dark Rum

My line of thinking went like this: if Champagne worked, why not something even more acidic… like rum?! As you can see in the image above (and as I found out later when researching this), alcohol interferes with gluten in dough. I could tell just from the mixing process that this dough would suck – it was crumbly and inelastic, and too much stretching would cause it to tear easily. But, I baked it anyway, and for my commitment, I was rewarded… it turns out that Bacardi pizza will self-flambe after 30 seconds or so of baking in a 550°F oven! The pizza ignited in a poof of blue flame, then flames gently danced around the perimeter of the dough for the remainder of the baking time. This pizza was giving off plenty of gas, as you can see by the pocket of lifted cheese in the 15-minute rest trial in the image above. Unfortunately, the dough just couldn’t hold on and the pizza ended up basically unleavened. The image below is a video frame-grab of the Bacardi pizza putting on a light show for me.

Finally, the winning recipe.

No-Yeast, No-Rise Champagne Pizza Dough Recipe

Inspired by the Modernist Cuisine at Home Neopolitan Pizza Dough recipe.

|

INGREDIENT |

QTY. |

SCALING |

PROCEDURE |

|

Unbleached All-Purpose Flour |

250g |

100% |

|

|

Champagne or Sparkling White Wine |

155g |

62% |

|

|

Honey |

10g |

4% |

|

|

Salt |

10g |

4% |

|

|

Vital Wheat Gluten (Bob’s Red Mill Brand) |

2.5g |

1% |

|

|

7.5g |

3% |

I love this idea!

What are your thoughts on using beer instead of sparkling wine? With some beers, the acidity would be much lower, but perhaps a gueuze or other lambic would achieve the desired effect?

Nice experiment. I wonder how tomato juice would work? Acidic and could add a lot of flavour. Doesn’t Modernist Cuisine have a recipe for Tomato water?

Brilliant. Where do I get the WRISE?

@Bri Beer would have been my next experiment, but my guess is that it would perform beautifully. A lambic is a great idea – I bet you could get some amazing flavors.

@Patricia Tomato juice is a fascinating idea! Tomato water is made by spinning tomato puree in the centrifuge and taking only the top, clear portion. I’ll have to give that a shot!

@Trevor – I got my WRISE by requesting a sample from http://www.thewrightgroup.net/products/products/wrise.html

Brilliant! The comparison photo is great, too. Given the flavor of the wine, What do you think of a lightly sweet pizza? Drizzle honey, cut up some fresh fig, goat cheese, fresh thyme…sprinkle of chopped walnuts? Have to look at the Flavor Bible and see what oddly wonderful combinations it inspires.

If the acidity is the rise-helper, and the alcohol the rise-killer. Maybe cider would work even better than sparkling wine.

Very interesting.

The resting time does more than just give the yeast time to work: it is when natural flavor develops in the dough and when the yeast action effectively kneads the dough.

So instead of skipping it, a good alternative (if you can plan ahead) is to make the dough the day before and then just put it in the fridge overnight. The resting time allows for enzymatic activity to create sugars out of broken starches, the yeast both develops the gluten (by the rise) and creates flavorful acidic components.

I don’t think alcohol inhibits gluten formation…it just doesn’t help it (unlike water). That’s why Cook’s Illustrated uses part vodka in its pie crust recipe…so that there will be less gluten formation and it will remain tender.

Finally, 4% salt is huge. (2% is more typical) But you may need that much to compensate for the lack of natural flavor due to the no rise.

@Beth Yes, a sweet pizza for sure! I like where you’re headed 🙂

@T. Yes, cider would likely work very well. I could also remove the alcohol from the champagne with the rotary evaporator and likely get even more rise.

@Allen Note that there’s no yeast in these recipes. It’s not to say that I don’t like yeast dough (I do), but to challenge the convention of relying on yeast for leavening in this type of dough. Also note that the Cooks Illustrated vodka method is specifically there do destroy glutenous activities. In pie, you want a flaky crust. Flakiness, in this context, is the opposite of elastic, glutenous chewiness. See this article for a snippet of how alcohol and gluten interact http://chestofbooks.com/food/science/Experimental-Cookery/Gluten-And-Dough-Continued.html. Also, you’re right that 4% is a lot of salt. You can take it down to 2% no problem, but I prefer a saltier crust when using as bland a cheese as mozzarella.

This is a fantastic idea!

Yesterday night, I had pizza and prepared it “conservatively” using flour, fresh yeast, salt, olive oil and liquid. I have no idea where I can get a similar microencapsulated leavener product over here in Germany…

Anyway, as for the “liquid” component, I prepared one dough with sieved tomatoes and the other one with pilsener beer.

Verdict: The beer dough turned out fine, but had a slightly bitter flavor which – at least in my opinion – doesn’t really go so nicely with the usual toppings (I had tomatoes, ham mushrooms and cheese). Probably one would have to select more appropriate ones to make this one a winner

The tomato pizza was fantastic! Not only did it look cool with its red coloured dough, but it also gave the pizza’s overall flavor (same toppings btw) some sweetness and more intensity. This is definitely a winner and I am planning to do some more experiments with more carefully selected toppings and different intensity (might add some tomato concentrate).

Thanks again Scott for your great ideas on pizza improvement.

Scott,

great idea and I look forward to giving it a go. Could you please elaborate on the “850°F grill-turned-pizza-oven”? Any info on how I can avoid building a forno yet still get that blast furnace style result would be greatly appreciated.

take care

Hey there,

This really seems like a delicious and easy idea, I just tried making a simple margarita and it tastes simply delicious. Do you have any idea how I could make this using that kind of style, mine just went from uncooked to ashes.

Thanks,

Andrew

sodium aluminum phosphate?

I have never, ever seen a recipe where aluminium are added on purpose. That is before I googled it now.

Fortunately, it seems as it is not as dangerous as I thought.

Unbelievable the efforts you made with this test! My next Pizza will contain Champagne that’s for sure ; )

Instead of using all-purpose flour and adding gluten, you might try a high gluten flour. GM’s All Trumps (I prefer the unbleached and unbromated version), King Arthur’s high gluten flour (Sir Lancelot?), and Honeyville Farms Imperial Hi-Gluten are all very good for pizzas and bagels.

-Mike

I wasn’t able to find retail quantities of Wrise, so I asked the nice folks at Modernist Pantry to carry it. They notified me that they’re stocking the regular, low-sodium, and aluminum-free versions now.

https://www.modernistpantry.com/wrise.html

Pingback: Pizza Trial and Error

Pingback: How Do How To Make Homemade Pizza Sauce Thicker | Pizza Cooking

Pingback: New Pizza Recipes Sanjeev Kapoor | Pizza Cooking

Pingback: Will The Recipe For Dough Pasta | Pizza Cooking

Pingback: Wil Healthy Baked Donut Recipes | Pizza Cooking

Pingback: Find Mini Pizza Cooking Times | Pizza Cooking

Pingback: Why Do Garlic Mashed Potato Pizza Recipe | Pizza Cooking

Pingback: Mastering the art of pizza – Mi pizza margarita favorita se llama rosita. - Alimentarte

Pingback: Cheesecake & Pizza Dough | CrazyFashion

Pingback: Eight Lessons for Living a Creative Life and Making Creative Pizzas | Chicago Ideas Blog

Pingback: No Yeast Wheat Pizza Dough | ABC Pizza Cooking

Pingback: No Rise Pizza Dough For The Grill | allaboutbbqs

Pingback: Why 2012 Was My Most Epic Year Ever - Seattle Food Geek

Pingback: Passover Pie – Adam Shostack & friends